Plug-in hybrid usage data compiled by Geotab shows limits of PHEVs’ economic and environmental value for commercial fleets

According to Geotab’s data, fleets operating PHEVs are relying on gasoline power for 86 per cent of their distance travelled.

Plug-in hybrid usage data compiled by Geotab shows limits of PHEVs’ economic and environmental value for commercial fleets

New data from a Geotab analysis of 1,776 North American plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) shows that, in commercial settings, PHEV fleets are making a dismally small dent in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

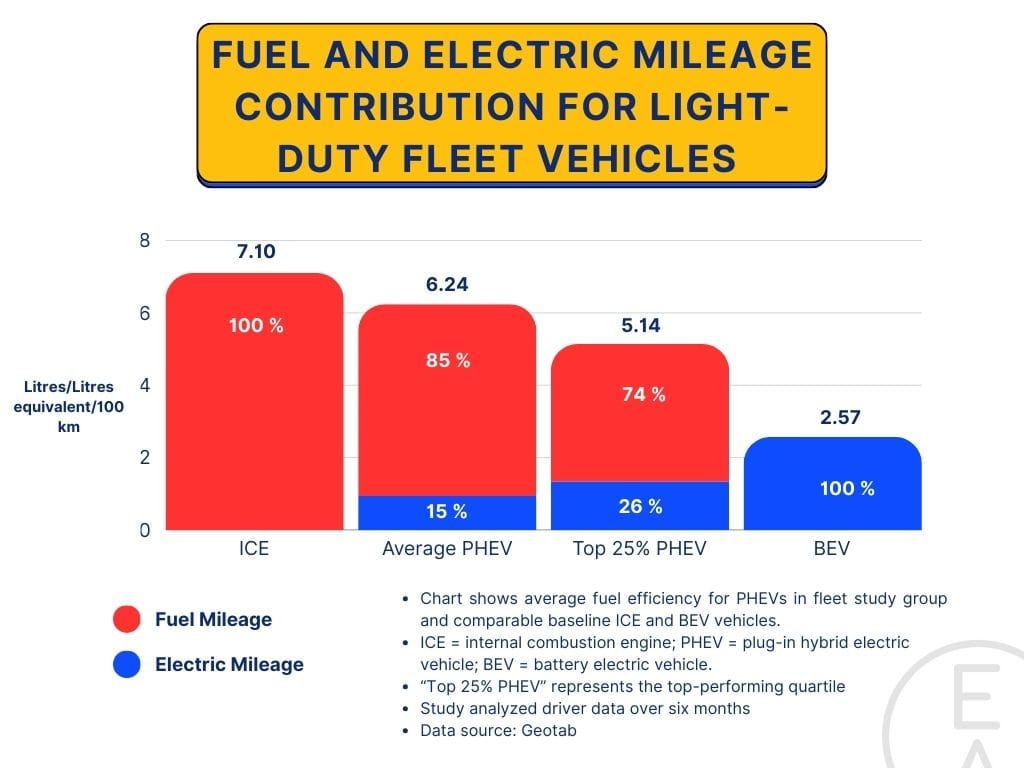

According to Geotab’s data, fleets operating PHEVs are relying on gasoline power for 86 per cent of their total energy needs. That translates into an average fuel efficiency for those vehicles of 6.24 Le/100 km — only slightly less than the 7.10 L/100 km achieved by their internal combustion cousins.

These findings align with a growing body of data in the United States and Europe that shows a significant disparity between the emissions-reduction and fuel-savings potential of PHEVs and the reality of how they’re actually used.

For example, in a report from the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Climate Action published earlier this year, carbon emissions from PHEVs were 3.5 times higher than what standardized regulatory tests showed. Likewise, a study by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) published in 2022 showed real-world fuel consumption for plug-ins may be 42-to-67 per cent higher than assumed within EPA’s labelling program for light-duty vehicles.

Far-reaching implications

The implications are far-reaching. For fleet operators, it means lost savings that would otherwise be achievable if they maximized their PHEVs’ electric range. (On a recent trip to my Hyundai dealership, I spoke to one Tucson plug-in driver who boasted he only filled his tank every two months.) Operating in this manner, most fleets won’t see a return on the cost and complexity of maintaining a vehicle with both a combustion and electric drivetrain.

More broadly, such findings call into question the effectiveness of government climate policies that include incentives for PHEV purchases, along with allowing them to zip along in high-occupancy vehicle lanes.

Why are these vehicles not fulfilling their promise? In Geotab’s analysis, it observed that 17 per cent of all PHEVs in fleets were not charged at all in the last six months and only 18 per cent charged at least once every 100 kilometres. Considering that 60 per cent of the vehicles analyzed travelled less than 100 km per day, this indicates that the majority of fleets are defaulting to using them like (very pricey) gas cars.

This would be like carrying around a reusable water bottle only to fill it up with bottled water.

“If fleets are going to invest in PHEVs, the way that they get the best return on investment for these assets is to maximize the electric energy, which of course costs less than gasoline,” says Charlotte Argue, senior manager, sustainable mobility at Geotab. “They are doing themselves a disservice to not try to maximize the charging opportunities as well as the electric driving.”

The discrepancy might be that fleet drivers have little motivation to make the switch from pump to plug when the company pays for fuel. Or as Argue suggests, “It may be that the company hasn’t invested in sufficient charging for their vehicles.”

Higher fuel efficiencies possible

The good news is that the top quartile of PHEV fleets in the Geotab study (the top 25 per cent in terms of electric range usage) are achieving larger fuel savings and significant emissions reductions.

Breaking it down further, the average fuel efficiency of an SUV or other multi-purpose vehicle in these top quartile fleets is 5.73 Le/100 km, versus 11.25 L/100 km for an internal combustion engine vehicle — almost 50 per cent more efficient.

“If we look at the fleets by segment, public works and municipal-type fleets are utilizing their electric energy in a better way — they probably have a charging strategy that came along with their decarbonization plans,” Argue points out.

Jennifer Kube-Njenga, program manager for fleet operations, engineering & public works at the City of Richmond, explained her approach in a recent session at the EV & Charging Expo: “The data speaks. We just put some PHEVs into our fleet and we can track who’s fuelling and who’s not fuelling and who needs a refresh on how to operate the vehicles. We had people who were just fuelling and weren’t using the battery on the unit and we had people who weren’t fuelling since they got the unit. Now that we’ve had the opportunity to educate, those fuel usage rates have come right down.”

Fleet managers who want to get the most out of their plug-ins can use tools like charging reports and an analysis of fuel use versus electrical energy use by vehicle. “Having data and metrics are a way for fleet managers to take action on underperforming vehicles. It’s so critical to have that feedback loop,” Argue explains.

Even more sophisticated fleets can implement geofencing to see when a vehicle comes back to a location and parks but doesn’t plug in, which can trigger a text notification or a flag to the driver or the facility manager. Organizations should also set up reimbursement plans to encourage drivers who plug in at home, even on a standard outlet, so that they don’t have to foot the bill.

Picking the right platform

In many cases, however, the best option is to steer clear of PHEVs entirely and buy full battery electric vehicles (BEVs) instead.

“While fleets can see some improvement in their total fuel use by choosing to purchase PHEVs, there is a lot more opportunity with battery electric vehicles,” Argue says.

Are fleets mistakenly choosing the wrong vehicle platform in their attempt to toe-dip in electric technology with a plug-in? Likely yes.

As Argue noted in a recent Geotab report: “In Canada, 82 per cent of light duty fleet vehicles we analyzed (over a year) have daily driving distances that could be satisfied by battery-electric vehicles. That tells us that the way light-duty vehicles in fleets are being operated today, the majority of them have duty cycles that are well suited for battery electric, and 50 per cent at a lower total cost of ownership over seven years.

“So the recommendation is to go BEV first because that’s where they are going to see the biggest improvements. If the objective for the fleet is climate action, then BEV should be the first pass to say no to.”